Tracking Oysters Along the Tides in Coastal Connecticut

August 8, 2025

Yuqing Chen is a doctoral candidate in natural resources and the environment whose summer research focused on natural intertidal oyster beds primarily through work on Connecticut’s shoreline.

Describe the location of your field research.

My field sites span the Connecticut coastline, from Greenwich in the west to Mystic in the east. They include natural intertidal oyster beds where we collect juvenile oyster (spat) that settled in 2024 and also deploy bags of oyster shells to capture spat settling during summer 2025.

What’s the focus of your research?

I use genomics to study evolutionary processes in marine populations to inform conservation and restoration. Funded partly by the Graduate School’s research travel grant, I focus on investigating how domesticated oysters recruit into and interbreed with wild populations and what this means for the evolutionary viability and long-term sustainability of oyster populations.

What do you hope will be the impact of this work?

This work documents an often assumed but almost undocumented ecosystem service of oyster farms: spillover recruitment subsidy to declining wild populations. By genomically measuring the temporal and spatial extent of this process in Connecticut’s eastern oysters and assessing potential trade-offs reflected in genomic patterns, this work will inform sustainable management strategies that create synergy between aquaculture and restoration of this ecologically and commercially important species.

How will field research advance your understanding of your research in a way that classes and/or theory do not?

Fieldwork allows me to test my hypothesis in real-world conditions by observing the oyster beds firsthand, collecting valuable samples, and gathering genotyping data. Field research in coastal Connecticut is essential because the region’s robust wild oyster populations support a growing aquaculture industry, which is transitioning toward increased use of hatchery-produced seed. This provides a unique opportunity to test how aquaculture oysters recruit into wild populations–making the first geographically extensive study on an open coast.

What has surprised you about your experience?

How deeply local communities and stakeholders care about oyster populations and coastal ecosystems. They are actively engaged and eager to support research and conservation efforts.

How did Cornell programs and/or faculty mentors help connect you with the opportunity to carry out this research?

My advisor, Matt Hare, has been incredibly supportive–he helped connect me with local stakeholders and collaborators who were essential in identifying field sites, securing access, and navigating collection permits.

What would you say to students considering applying to Cornell for grad school?

The range of research at Cornell keeps you intellectually engaged. You build a supportive community that shares opportunities, offers feedback, and helps navigate your career. I’ve appreciated the flexibility of my program, the expertise of my graduate committee, and the kindness of peers, staff, and faculty. Reaching out to potential advisors early is worthwhile—those conversations can clarify expectations and help determine whether the program is a good fit.

Photo Captions and Credit

Photo 1: Yuqing Chen measures salinity and temperature near an oyster reef in Jarvis Creek, Guilford, Connecticut. In the background, two oysters shell bags are being deployed at low tide to collect settling juvenile oyster spat over the summer. Photo courtesy of Harmony Borchardt-Wier.

Photo 2: Associate professor Matt Hare (left) and Yuqing Chen (right) deploy oyster shell bags at low tide at a coastal site in Stratford, Connecticut. These bags are intended to collect juvenile oyster spat during the summer settlement period. Photo courtesy of Harmony Borchardt-Wier.

Photo 3: Yuqing Chen records salinity and temperature data beside an oyster reef in Goodwives River, Darien, Connecticut. In front of her, two oysters shell bags are being deployed to collect juvenile oyster spat expected to settle over the summer. Photo courtesy of Matt Hare.

Photo 4: Matt Hare, associate professor in natural resources and the environment, holds a bucket of juvenile oyster spat—young oysters that have attached to shells or other hard surfaces—collected from an intertidal oyster reef in Old Saybrook, Connecticut. Photo courtesy of Harmony Borchardt-Wier.

Photo 5: Harmony Borchardt-Wier, a lab manager in natural resources and the environment, collects juvenile oyster spat—young oysters that have attached to shells or other hard surfaces—from Jarvis Creek, Guilford, Connecticut, at low tide. Photo courtesy of Matt Hare.

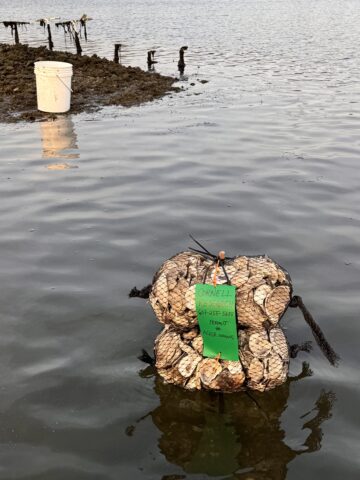

Photo 6: Two oyster shell bags deployed at Ash Creek, Fairfield, Connecticut, aiming to collect juvenile oyster spat expected to settle over the summer. Photo courtesy of Matt Hare.